Counterspace’s Sumayya Vally ON Identity and design form

During Milano Arch Week at Triennale di Milano, Sumayya Vally presents the research and ideology behind the work of her design studio, Counterspace. The Johannesburg-born practice explores spaces between the functional and the speculative; using research from ‘our identities, our cultures, our ways of being,’ to form architectural expressions. ‘We have to question what we’re doing and what the purpose is behind it. It needs to be guided by some form of integrity,’ the architect and principal of Counterspace tells designboom.

Sumayya Vally’s presentation at Milano Arch Week | image © FTfoto, courtesy of Triennale Milano

early career and Fouding Counterspace

Born in 1990, Sumayya Vally began her professional career in architectural education, leading the University of Johannesburg’s Unit 12, An African Almanac, at the Graduate School of Architecture. The unit was founded by Professor Lesley Lokko, with the intent to create a curriculum for the African continent. Vally co-founded the practice Counterspace in 2015, inspired by the city of Johannesburg and the resilience of it’s people. The studio’s work varies across research, the built environment, and curatorial works, ranging from the design of the Serpentine Pavilion in 2021, to curating the Islamic Arts Biennale 2023, and contributing to the main exhibition of the Venice Architecture Biennale 2023 with the African Post Office. Read the interview in full below.

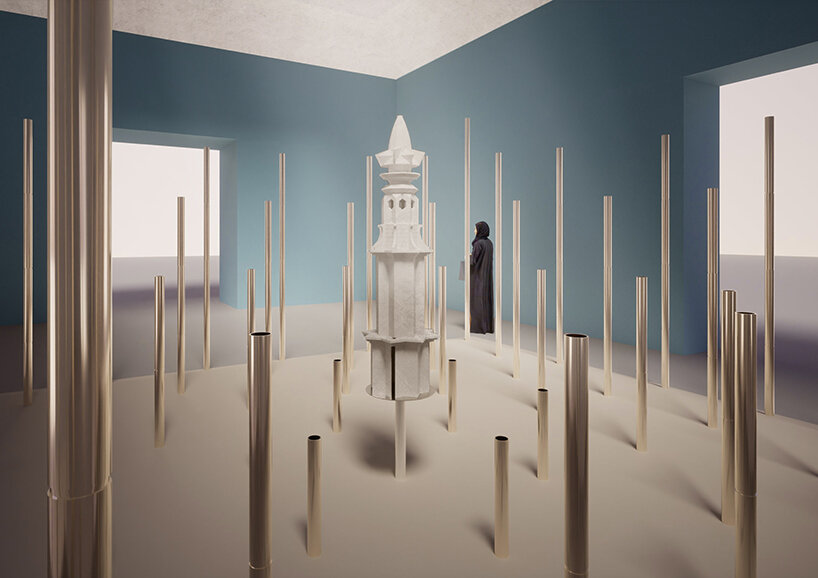

Islamic Arts Biennale 2023, scenography by OMA | image © Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of OMA

Interview with Sumayya Vally

designboom (DB): Can you please introduce Counterspace and the kind of work you do?

Sumayya Vally (SV): I am the principal of Counterspace, based between Johannesburg, London, and Jeddah. My practice is interested in finding design form and design expression for our identities. The practice was started in and is formed by Johannesburg, and I believe that there are so many design forms, waiting to come from our identities, our cultures, and our ways of being. At the time when the practice was started, I felt that Johannesburg had so much to offer in terms of imagining different architectural languages. I didn’t see those languages reflected in the profession. Counterspace began as a response to this, as a space to imagine what cultural typologies for the African continent looked like. Subsequently, that’s translated across geography to many other places, because that lens is very relevant. Our identities are hybrid and because of history they are incredibly entangled. We we all have parts of each other inside of ourselves.

OMA designed the exhibition spaces for Islamic Arts Biennale | image © Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of OMA

DB: How do you approach your work, and has your work method changed since the early days of your practice?

SV: I don’t think the method has changed. I don’t think the intention has shifted, but the means of output have expanded over the years. The practice has always intended to find design form and expression for identities and to consider the generative potential that’s been locked in place. That includes everything from the color of sunlight in a space, to the cultural and material histories of a context. We work almost like an archaeologist or historian to think about how these historical impacts, some visible and some invisible, take a presence and manifest on a site. My first part of the process is a deep and intense procrastination, to delve deeply into as many facets of the site as I can find.

I think that in the design processes, there sometimes becomes one strand that becomes the guidance for the conceptual food of the project. But, the more that one reads and researches, the more that other strands also resonate with the project. Part of the process of design is understanding, and drawing is just transmitting and translating some form of understanding. In the process of drawing there are things that come to the surface.

the 120,000 square meter event took place in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia

image © Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of OMA

DB: Your portfolio also involves curatorial work, would you be able to expand further this work that Counterspace have completed?

SV: For the Islamic Arts Biennale, it was the first time I curated something at that scale. The project is 120,000 square meters. In terms of a platform for finding design form and expression for our identities, seeing cultures as generators for design expression, and for representation of who we are in artistic and creative form, it completely resonated with what our practice is doing. I don’t make distinctions between built things and curatorial processes because there is often overlap. The practice is guided by purpose and intent, and if a project is meeting those intentions, it becomes very valuable to take on as a process.

The curatorial work has been deeply pedagogical in that it is like design research. The process involved collaborating with the artists, working on the conceptual framework, imagining what the definition of Islamic art should be, a definition that is performance lead and thinks about generations of material culture, how they’ve been inherited, and how we can evolve them into the present ecological frameworks, our understandings of what it means to sustain culture, our existence, and our ways of being with other species. I think that there is so much that is waiting to be generated from these philosophies. It felt incredibly pertinent as a research project because there are so many themes that I have learned and know that shall live in on in my practice.

spaces are sheltered beneath the canopy of the Western Hajj Terminal, designed in 1981 by SOM

image © Marco Cappelletti, courtesy of OMA

DB: Can you describe the contribution that you made at Venice Biennale this year?

SV: It’s a very humble and modest research project. It’s called ‘The African Post Office’. It’s a study of different totem typologies through history, we looked from Southern Africa to Northern Africa and diasporas. One configures the map at the simplest gathering and convening structures, which are often totem structures that are used for ancestral ceremonies. It’s really a very simple typology that is somehow common across cultures and does the work of very hefty architecture, in that it brings people together.

The African Post Office at Venice Architecture Biennale 2023

DB: What are your ambitions for Counterspace in the long-term future?

SV: What I’m deeply interested in, and what all the work points to between the curatorial work, the boat project, and the installation, is how we think about the future of cultural typologies. I think cultural typologies are fraught in that they are infrastructures that were built to house certain forms of identities or loot from other identities. If we think about how different cultures honor, celebrate, and have festivals, there is very much a living and breathing experience in that. How we think about forms of architecture to resonate and respond to these dynamic forms, for me, is very inspiring. I’m not just talking about a programmatic level of accommodating a performance space, but thinking about how we can generate architecture that is entirely guided by different forms of gathering, that doesn’t set up the same kind of hierarchies that we have at present.

Many of my projects at the moment are in that space. Even in projects like the pedestrian bridge, it somehow still becomes about culture and spaces for gathering and thinking about how identities live in the built environment. Project by project, trajectories have also started to emerge. The intent when the practice started was to find design form an expression that embodies Johannesburg, now it’s design form and expression that embodies the conditions of a place. In that case, it is an evolving trajectory. But somehow I think that if you look at what you are doing now, it’s the same thing that you were always doing, even if you think you were not, I feel like that.

Asiat-Darse Bridge in Vilvoorde, Belgium

DB: Your work has a lot to do with breaking down societal hierarchies. Your individual career mirrors this by breaking down architectural hierarchies in achieving success young in your career, could you reflect on the early stages of your career and what you define as architectural success?

SV: I never thought about success at all, it’s something that as a young practice, especially from a context like mine that deals with so many legacies of economic segregation and generational deprivation, I should have. I didn’t think about success in any terms, but I was motivated by an inner-purpose and inner-desire to work with and learn from Johannesburg. When I started the practice, I was working full time in a museum and narrative practice, and I was teaching full time. Those incomes supported the research endeavors that the practice had and I worked on several research projects for the city of Johannesburg.

Slowly, the practice became more of a full-time endeavor, but it took a long time and a lot of work and sacrifice. I don’t think I’ve ever been motivated by visibility or success. It feels to me like it’s somehow like a trap, to work in the image of success, because if one is doing that to determine their trajectory, it means that one is following someone else’s success. And I don’t think that one person can attain a level of success that is someone else’s path. If someone has achieved a trajectory, it’s because they followed who they are, what they have to say, and the inner-purpose that they needed to pursue.

‘the project is a pedestrian bridge that connects two sides of the city’

(SV continued): I evaluate the things that we work on and the next steps of practice in terms of that inner-purpose, because I think it’s a misnomer to chase success without following purpose. I think that it’s also dangerous. I feel like our generation is very motivated by success and that worries me for the future of architecture, because there are so many wrongs that need to be righted. Certainly, we all need to see ourselves represented, we all need to take up more space, we all need to be compensated accordingly. But, I think if we are thinking about success, we are only considering the short term and that means we’re thinking within our lifetimes which is on some level superficial. You know the saying, ‘a society grows great when old people plant trees in whose shade they know they will never sit.’

If one wants to be successful, short term, their aim of success is then in the image of something that already exists. But to be able to sustain, and to make change, one has to stay the course, undo, and do a lot of work in the background that is about systemic change. It’s not enough to put change as a face, and for example, to put people-of-color in positions, when actually the system is deeply broken. It’s actually doubly oppressive, because it means that people-of-color perpetuate the oppression. I’m not saying that everybody must suddenly change everything at once, because it’s not possible to do that. But, in every platform, we have to question what we’re doing and what the purpose is behind it, and it needs to be guided by some form of integrity. And that is a long game that will go beyond our generations and our lifetime.

the project references water architecture from the Congo, where Paul Panda Farnana was from

DB: What upcoming projects are you working on at the moment?

SV: We are working on a project for a bridge in a city called Vilvoorde, in Belgium. The brief for the project was to design a pedestrian bridge that connects two sides of the city. When we got the brief, I started researching the city of Vilvoorde and specifically focus on its migrations, because of its position on the waterways. Throughout history, Vilvoorde has been a place where people have come or been brought.

I found in the research, this figure named Paul Panda Farnana, and he is an incredible man who came from the Congo. He was intelligent, he studied horticulture in the town, passed with distinction, and his research made a contribution to what the landscape of Belgium looks like. He also worked in the Congo, with the landscape there. He was also a political advocate, he fought in the war for Belgium, and yet he experienced first-hand discrimination and violence towards black people, even though they were fighting the country that was now their home. After that, he started to speak up about this discrimination, he organized Pan-African and liberation conferences all over Europe. With Du Bois and several others, he advocated for the wages of black people to be more fair, and he took the story of the discrimination and unfair treatment around the world as far as he could. He was very sadly poisoned and assassinated at the end of his life. I felt very inspired by the story of this person, who I’d never heard of, and wanted to create a project that honors his life and his legacy, while also honoring the legacies of 1000s of people who are unnamed and unknown.

For the form of the project, one of the research strands was water architectures from the Congo. In some of the research images, we saw beautiful boat structures configured next to each other, which then became platforms for people to trade, gather, and share. The bridge takes the form of these boats and each of them are planted with species that come from Farnana’s research. Then, there are auxiliary boat structures that will embed themselves across areas of the riverbank, which will pollinate industrial areas across the landscape, as well as being a metaphor for healing. Each one will become a little garden of reflection and will be named in honor of the names that we found on the slave register.

project info:

designer: Sumayya Vally

studio: Counterspace | @_counterspace

featured projects: Asiat-Darse Bridge | Islamic Arts Biennale 2023 | The African Post Office

event: Milano Arch Week

dates: 2 – 11 June 2023

ARCHITECTURE INTERVIEWS (247)

COUNTERSPACE (5)

MILANO ARCH WEEK 2023 (3)

PRODUCT LIBRARY

a diverse digital database that acts as a valuable guide in gaining insight and information about a product directly from the manufacturer, and serves as a rich reference point in developing a project or scheme.